Meet the Sheffield artist capturing the city’s quiet, uncanny corners after dark.

Could you tell us how you first got involved in art and any of your early artistic influences?

I was born in Bristol and grew up in Blackpool. Art outside of school wasn’t really part of my background, though my folks were creative in their own ways. I did the odd doodle and illustration, but it was at school that I realised I had a knack for it. My high school art teacher, Mr Carroll, encouraged me to push further. Still, being at an all-boys comprehensive school, I was steered towards STEM subjects, so I ended up doing A-levels and then went to Bangor University in 1990 to study mathematics. I lasted six months. Ironically, it was at Bangor that I really started painting – landscapes at first, views of Snowdon that I could see from the halls of residence – and began building a portfolio of sorts.

When I dropped out, I went back to see Mr Carroll. On the Monday, he told me to bring in all my drawings. By Wednesday, he’d booked me an interview at the local art college foundation course. By Friday, I’d been accepted. That week changed my life. I spent two years on the Blackpool foundation course, which gave me the grounding to go on and study Fine Art at Sheffield Hallam in 1993.

My early influences were Magritte’s surrealism, De Chirico’s metaphysical strangeness, and Yves Klein’s minimalism. Over time, that’s broadened. You can still see De Chirico in my work, but now I’d add Andrew Wyeth’s magical realism, Edward Hopper’s lonely stillness, and Gregory Crewdson’s photographs of unnerving townscape atmosphere. Those threads run through the paintings in my current Cupola show – ordinary spaces charged with something uncanny, where the familiar becomes unfamiliar.

How has your style or approach evolved since you first started creating?

At uni, I was encouraged to work in the anti-painting styles of the time, ending up making very dry monochrome canvases with text on. A trip to San Francisco in the mid-90s changed my view of what art could be. I realised painting could be expansive and emotional – people were painting everywhere: street walls, inside hallways, advertising – not just the dry, cerebral, conceptual work I was used to.

After university, I worked all sorts of jobs, eventually spending a decade at Waterstones. Surrounded by books, I researched, absorbed and taught myself through what I could get hold of. In 2008 I pushed myself to start showing portraits on a stall, and in 2009 I was asked to make a portrait of the Moor in Sheffield. I couldn’t pin it down to one image, so I created a constellation of square paintings, each showing a different aspect. This opened the door to cityscapes being a subject.

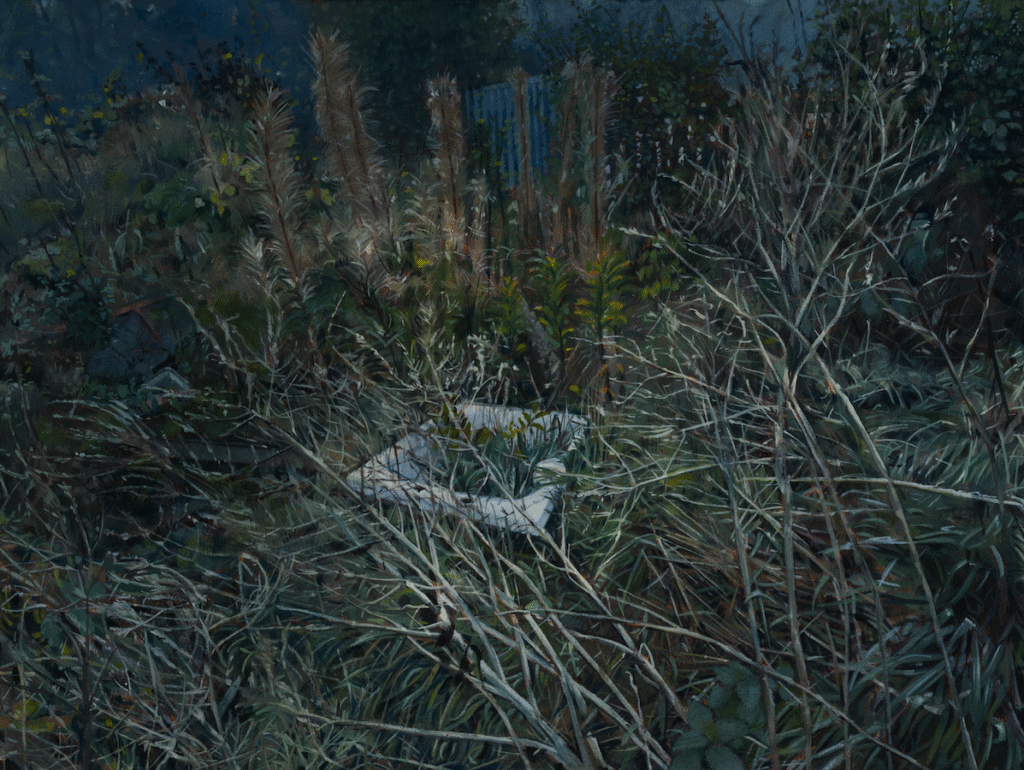

In the early 2010s, I began walking the city and found myself drawn to marginal places and spaces – empty shopfronts, car parks, backstreets, half-lit corners – that carried a strange tension. That’s when I came across the word kenopsia, in John Koenig’s The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows Tumblr blog: the eerie atmosphere of a place usually full of people but now empty. It described exactly what I was painting. Since then, my work has been about those overlooked corners of Sheffield, especially at night. I’m not expressly interested in photorealism. I want my painting marks to stay visible, while letting what I’m painting be clear. My approach has shifted from conceptualism to something rooted in realism, but it’s always been about reconstructing what I felt in a moment – creating a connection and meaning as I construct the painting.

Where do you tend to find inspiration – and how do you stay inspired when things feel flat?

I find inspiration in the act of looking. It’s rarely the big, obvious scenes that spark me, but the small shifts – the flicker of a streetlight on a wall, the way a street feels different after rain, or how a building seems to hold itself differently in the light of night. Those moments stay with me, and I’ll carry them back into the studio.

When things feel flat, I remind myself to slow down and pay attention. To stop getting caught in my head. I’ll head out on a walk with no plan, just to see what Sheffield offers. That process of noticing – of giving weight to what’s usually ignored – always brings me back to painting

That’s when I came across the word kenopsia: the eerie atmosphere of a place usually full of people but now empty.

Is there a dream project or collaboration you’d love to take on?

I’ve got two ideas that keep circling back. A few years ago, I worked on The Inner City Round Walk of Sheffield by Terry Howard – a 12-mile route that threads through the city’s suburbs, industrial heritage and hidden corners. I’d love to return to that project and build a deeper relationship with it, making work that responds directly to the walk, section by section, so the paintings become a kind of companion to the journey.

The other idea is more open. I’d like to create a project where I ask people about their own relationships with Sheffield – the odd, obscure places that matter to them, the corners that carry memory or atmosphere. Then I’d make work from those stories and observations. It would open Sheffield out into something more than just my view of it, layering my perspective with the city as others live and feel it.

How would you describe your work to someone seeing it for the first time?

I’d describe my paintings as realist works that focus on Sheffield at night, but not the obvious or celebrated views – always absent of people, suggesting a freezing of a moment in time. They’re about the city’s quieter corners – streets, shopfronts, car parks – that often go unnoticed, yet seem to hold memory and atmosphere. What I’m aiming for is a sense of stillness and tension, where the familiar feels slightly estranged, as if the place itself is holding something back.

Though obviously I use photography, the paintings aren’t about strictly reproducing a photograph. I want the brushwork to stay visible. The errors are important – they give the surface life. The painting is made by a human being, not a machine.

What advice would you give to aspiring artists?

Be curious and keep looking. Read, walk, notice things, and let yourself be influenced by what’s around you. It doesn’t have to be grand – sometimes it’s the smallest detail that opens up a whole new direction.

And finally, be patient with yourself. Art isn’t a straight line. There will be flat patches, detours, and times when you feel stuck. That’s all part of it. Keep going, keep paying attention, and hopefully the work will carry you through.

Paintings by Andy Cropper can be viewed at Cupola Gallery until 15 November.

@andycropperart