I grew up in Ecclesfield, the north of Sheffield, and I’ve pretty much lived around here all my life. My dad played guitar and was in bands, so music was always in the background. I remember watching him sound-check at The Ball in Ecclesfield, being surrounded by speakers and noise. I found it all a bit mesmerising.

He wanted me to learn guitar too, but I’ve got short, stubby fingers and no patience, so it never really worked out. I always had a lot of energy – probably undiagnosed ADHD or something like that – and drums just made sense. I liked hitting things. It was a proper outlet for me, a way to get stuff out of my system. I was definitely one of those kids who couldn’t sit still, never happy being stuck in a classroom.

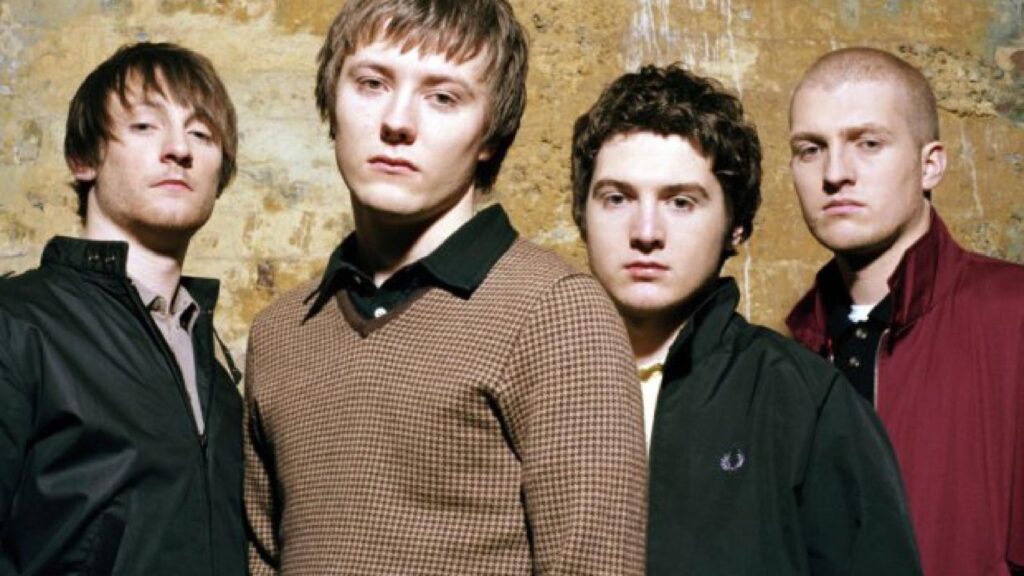

Growing up, I was more into football than music. I played for Ecclesfield Red Rose, and that’s where the members of what would become Milburn first met – me, Tom, Louis and Joe. I went to Ecclesfield Secondary with Tom, while Louis and Joe went to Notre Dame, but we were in all in touch through football, and the idea of playing music together was floated at some point. Funnily enough, I went from playing football with Billy Sharp at secondary to a practise room with Alex Turner and Matt Helders at college. Only in Sheffield, eh?

My first kit was a black Olympic that me and my dad found in the Ad-Mag. I’d saved up about £200 from cutting grass and washing cars, so we went over to pick it up from somewhere near Nether Edge. We set it up in my nan’s loft in Ecclesfield. She had a house with loads of space, no neighbours nearby, so we could make as much noise as we wanted. That’s where it all started, really – me, Tom and Louis practising up there. Joe got roped in later as the bass player and singer. He was the younger brother who didn’t really have a choice.

I was about 13 or 14 then, still at school. We started going into town to play gigs at places like the Boardwalk and the Grapes. Because we were all underage, we had to hire venues ourselves and sell tickets to our mates. It was proper DIY. We weren’t thinking about record deals or fame – it was just something to do after school.

When we got to college, that’s when it started feeling like something more. Around that time bands like the Strokes were breaking through, and their sound felt really accessible. You could learn a song in a practice session, and it gave you confidence to try writing your own. I was at Barnsley College doing music, media and computing, but all our spare time went into the band. We were full of energy, increasingly convinced that if we just kept pushing, something would happen.

We started recording at 2Fly Studios with Alan Smyth. Arctic Monkeys were around then too – Geoff Baradale, their manager, actually first saw them at one of our gigs. The scene in Sheffield was buzzing. It felt like everyone was in a band or starting one. We got signed to Mercury Records when I was 18. We could’ve signed earlier, but Joe had to finish his A-levels. It’s crazy looking back and realising how young we were.

Some of the songs that ended up on Well Well Well, our first album, were ones we’d written back in my nan’s loft when we were 14. ‘Cheshire Cat Smile’ stands out as one of those early ones – it still has that teenage innocence about it, a bit rough around the edges but full of life.

We toured loads after that and had some incredible moments. Japan was wild – we went over with The Rifles first, then went back on our own. We even played Fuji Rock. The crowds were amazing. You’d finish a song and they’d all clap for five seconds, then go completely silent. You could hear a pin drop. It wasn’t like gigs back home where we were watching lads getting chucked up in the air – far more polite.

It was a mad time. The Monkeys were flying, and we were caught up in that whole wave of noughties NME bands. I won’t lie, it was tricky sometimes being in their shadow, trying to carve out our own thing. Our second album, These Are the Facts, came with a bit of pressure. We recorded it down in Cornwall at a studio called Sawmills – you had to get there by boat. It was amazing, proper middle of nowhere place. Alan came down to produce it with us, and that gave it some of that 2Fly sound we loved.

But after a while, we started pulling in different directions. Tom and I were getting into heavier stuff, and that later turned into Backhanded Compliments and then Dead Sons. It wasn’t a big fallout or anything, just time for a break. The way it was announced made it sound more final than it really was. It felt like unfinished business, which is why the comeback years later meant so much.

After Milburn, I did a bit of everything. Bar work at the Washy, some session drumming for Reverend and the Makers, Tom Grennan, She Drew the Gun and Bill Ryder-Jones. I didn’t want a “proper” job – I still wanted to be around music. Teaching drums came about by accident. A few friends asked me for lessons, and it built from there. I don’t really think of myself as a teacher, though. It’s more like helping people start their own journey. I talk about drums, about feel, about what makes music tick. That’s the good bit.

I’ve recently started having lessons myself again with Steve White – Paul Weller’s old drummer. He’s been in the studio, too. It’s a reminder that you never stop learning. That studio – and the community around it – has become a focus for me now.

The Red Light Sessions came out of a simple idea: trying to capture those magic moments that happen in a rehearsal room when everything just connects. I wanted to bring together musicians who might not normally cross paths – young artists, veterans, people from different corners of the local scene.

We’ve had Steve Edwards, Rev, Ed Cosens, Bromheads, Goldivox and the Milburn boys in too. These musicians have played alongside up-and-coming artists from Water Bear Music College and the Tracks music project. It’s been brilliant. It’s about community, about rebuilding that spirit that Sheffield’s always had – bands supporting each other, watching each other perform. After sessions, I’ll sometimes see people swapping numbers, planning projects. That’s what it’s all about.

Each session is one take. We do an original song and a cover. The original goes out through Exposed, and the cover goes on Patreon, where people can support what we’re doing and get extra content. It’s a nice way of keeping it self-sustaining, and it gives up-and-coming artists something to show – like a mini audition reel for what they can do.

There’s a saying about ‘red light syndrome’ – back when recording was expensive, the red light would come on when the tape was running, and people would freeze up. That’s where the name came from. But it also fits because the studio’s based in Attercliffe, and there’s a certain connection there too.

I’m also planning a ‘Greatest Hits’ gig for it at some point – something that brings all these musicians together for one big night. That’s what Sheffield is for me: community, collaboration and a bit of chaos, all under one roof.

Check out the red light session Patreon here and on socials here .

Interested in doing a Red Light Session? Email RedLightExpo@gmail.com